photo taken by bysevensixfive

PLOT, [was] one of the most intriguing young architectural practices around, and now the two principals of each firm have split to form their own practices-JDS [Julien De Smedt] architects, and BIG [Bjarke Ingels Group]. they both originate from denmark, but have worked under the likes of rem koolhaas' OMA. PLOT initiated as a frantic and almost desperate attempt to enter as many architectural competitions as possible. some bit, but most didn't go past the conceptual stage. they even went as far as proposing [without being prompted *gasp*] a super-harbor that concentrated all shipping docks on denmark's entire coast into on giant station in the middle of the sea. this "superharbor" would also have a hybrid bridge/tunnel that would link denmark to the netherlands. see the entire video here. the music is a testament to these guys and that they don't take themselves too seriously.

what does this have to do with architecture, you say? easy: after all the old harbors have been redeveloped into housing, ALL danes can live on the coast. the danish government wasn't as intrigued with this idea as china. so now it has taken off to land in the east, in the shape of the country's 5-pointed star, rather than a 6-pointed starburst.

the rest of this article is excerpted from domus magazine [italy]:

After five years, three buildings, countless designs and much critical acclaim, Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt of PLOT have decided to go their own ways, founding BIG and JDS respectively. Domus presents PLOT’s most recent works. Text by Joseph Grima. Photography by Gaia CambiaggiNews that their competition entry for Helsingør Psychiatric Hospital had won first prize came as something of a godsend to Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt, co-founders of the now defunct architecture practice PLOT. It was February 2003, and the office’s other projects were either finished or on hold; office staff completed the competition entry as a gap-filler during their last three months of notice before closure. It was a hard-earned victory that followed an extensive period of visits and telephone calls to consultant psychiatrists, doctors, patients and hospital staff; Ingels describes the result as a “long list of conflicting desires, with no clear requirements”. Even the competition brief itself was an exercise in ambiguity, calling for a building both centralised and non-hierarchical, protected and secluded but open to its surroundings, introverted but not carceral, two-storey but with external access from every room. “After all,” Ingels quipps, “Helsingør is the hometown of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The brief was to be and not to be.”

The result is a low-slung starburst, a bundle of rectilinear wards and treatment facilities that meet in a central point of intersection. The sculpted landscape surrounding the building dips to reveal a lower floor where the patient’s rooms and additional accommodation for staff are located; the upper floors of the three wings are devoted to the treatment of the hospital’s patients. The architect’s main objective was to do away with the clichès associated with hospital design, such as dark, claustrophobic corridors crossing tightly-packed, symmetrically-arranged wards. Here the long, brightly-coloured corridors are lined with glass to allow maximum light penetration and to afford the occupants a “gallery of views”, a condition of constant visual contact with the exterior. Dotted around the three wings are a number of sunken courtyards that offer patients secluded and protected open-air spaces.

As with most of their work, the clover-leaf plan underwent innumerable alterations, adjustments, amputations and improvements during project development. This approach to design, which obstinately subjects as wide as possible a range of formal and programmatic iterations to a Darwinian fitness test, was inherited from OMA, where Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt first met. Their design strategy posits that every constraint exerts a force on the architectural artifact, and not necessarily for the worse; on the contrary, “optimised constraints” are seen as the tools that sculpt the unique identity of a successful design. Counterpart to this approach is the willingness to dispassionately substitute one programme with another while carrying out relatively minor alterations to the architecture itself: the design for Helsingør Psychiatric Hospital, for example, began its life as an unrealised proposal for an aquacentre.

The results of this anti-dogmatic process of tireless experimentation undermine the assumption that certain building typologies are incompatible with creative architectural expression. A recently-completed scheme in Ørestad, one of Copenhagen’s fastest-growning suburban neighborhoods, takes on the bête noir of contemporary European architecture: high-density, affordable, privately-funded housing developments.

The VM Houses (so called because in plan the south-facing block forms a “V” and the north-facing block an “M”) are the result of a very unexceptional brief calling for 230 residential units in 2 blocks combined with the constraints imposed by zoning height requirements, optimisation of views towards the nearby canals and sightlines from the surrounding residential neighbourhoods. The success of the project took even the Danish developer Per Høpfner by surprise: all units were sold out in just three weeks, most going on the first day they were put on the market. This exceptional result might well have something to do with the fact that PLOT’s design overcomes one of the less appealing characterstics of most housing developments. Rather than replicating the same apartment module throughout the blocks, the VM Houses constitute a 3D jigsaw puzzle of sorts, offering a bewildering variety of different floorplans (75), none of which is repeated more than a dozen times. Several, especially those on the top floors dissected by the sloping roof, have unique features such as outdoor terraces. Were it needed, more proof that the accepted rules of working with developers are not necessarily inflexible is granted by humourous touches such as the pixelated portrait of the developer (executed in brightly-coloured bathroom tiles) on the walls of the entrance lobby.

The architectural solutions proposed in the past five years by PLOT - and now carried forward separately by the offices of Ingels and De Smedt (BIG and JDS respectively) - habitually and ingeniously undermine the customary approach to urban intervention, as the unrealised projects on the following pages demonstrate. In addition to this, they are exploring new realms of intervention by taking a proactive stance in seeking new commissions: rather than relying on competitions or direct commissions to feed the office’s workflow, PLOT frequently offered univited proposals for large urban interventions to municipal authorities in Denmark and elsewhere, which were often received surprisingly warmly. Some, such as a proposal for a three-kilometre wall of apartment blocks that would surround an open area devoted to sports in the Klovermarken area of Copenhagen (quenching the city’s thirst for housing in one fell swoop), became the focus of heated political debate and petitions both in favour and against. PLOT’s great achievement is to have succeeded - in its brief five-year lifespan - in offering an example of an architecture practice capable of reconciling avant-garde design with the real needs of clients both public and private. It’s now up to BIG and JDS to find new areas of intervention and write the next chapter of the story. J.G.

Works In Progress

A selection of projects conceived by PLOT and now being developed independently by BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) and the practice of Julien De Smedt, JDS Architects

Mountain Dwellings, Ørestad

Mountain Dwellings is the second phase of the completed VM Houses project, and will be built on the same site by the same developer. Composed of 2/3 parking and 1/3 residential units, it merges these two programmes into a single building optimising views, daylight exposure, accessiblity and density. The apartments are arranged in a south-facing, sloped array supported by 11 storeys of car parking: the result takes on the appearance of a mountainside, standing out in stark contrast to Copenhagen’s flat landscape. Bjarke Ingels and Julien De Smedt describe the project as an excercise in “suburban living with urban density”.

People’s Building, Shanghai

The RÉN building is a proposal for a hotel, sports and conference centre for the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai. The tower, developed in association with ARUP, is conceived as two buildings that merge into one over a waterway. The first is devoted to the body and houses a sports centre and water culture centre, the second to the mind, with a conference centre. The point where the two buildings merge into one is devoted to a 1000-room hotel. After completing the design, the architects discovered a fortuitous likeness between the building and the Chinese character meaning “the people”, thus giving the building its name.

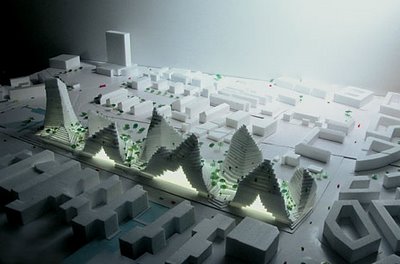

The Battery, Copenhagen

The Battery is a large-scale project for urban intervention that seeks to integrate three disjoined neighbourhoods of Copenhagen (Islands Brygge, Amagerbro and Ørestaden) by overlapping them in an “urban activity centre”. The new neighbourhood, several blocks in length, comprises all the basic elements of urbanity: apartments, offices, shops, child care and sports facilities and cultural institutions. By including a mosque (the first in Denmark), it also aims to favour the cultural integration of the city’s minorities. Although the new neighbourhood’s architecture appears to be of geological inspiration, the mountain-like buildings trace exactly the maximum buildable height of each plot, thus optimising the site’s density.

No comments:

Post a Comment